Hey folks, I know I said I'd return to regular blogging after the semester ended, but I am still busy working on cranking out My Spaceship. Does anyone know how long it takes to fold and sew 100 chapbooks? That's right, a long freaking time. I should be done within the next couple of days.

Had a swell time in Boston, catching up with everyone there. Then a fantastic reading at St. Mark's by Lara Glenum and Aase Berg. If you aren't familiar with Action Books, you should be.

May 30, 2006

May 16, 2006

Dearest Boston,

The Plough & Stars Poetry Series

featuring

Joyelle McSweeney & Mark Lamoureux

Sunday, May 21, 5:30 pm

We are pleased to announce the third event in the Plough & Stars Poetry Series, to be held on Sunday, May 21, 5:30 pm at The Plough & Stars, 912 Massachusetts Ave., Cambridge, near the Central Square stop on the Red Line. http://www.ploughandstars.com

Joyelle McSweeney is the author of The Red Bird and The Commandrine and Other Poems, both from Fence. She teaches at the University of Alabama and writes regular reviews for the Constant Critic. She recently co-founded Action Books (www.actionbooks.org), a new poetry and translation press.

Mark Lamoureux is a poet, critic and translator who lives in Astoria, NY. His work has appeared in numerous publications, both in print and online. He is an associate editor for Fulcrum Annual. He is the author of three chapbooks: City/Temple (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2003), 29 Cheeseburgers (Pressed Wafer, 2004) and Film Poems (Katalanche Press, 2005). His first full-length collection, Astrometry Organon is due out from Spuyten Duyvil/Meeting Eyes Bindery in the winter of 2006.

For more info contact:

John Mulrooney - jmulroon2002@yahoo.com

Michael Carr - cancelaspirin@gmail.com

Sincerely,

Yr Prodigal Son

The Plough & Stars Poetry Series

featuring

Joyelle McSweeney & Mark Lamoureux

Sunday, May 21, 5:30 pm

We are pleased to announce the third event in the Plough & Stars Poetry Series, to be held on Sunday, May 21, 5:30 pm at The Plough & Stars, 912 Massachusetts Ave., Cambridge, near the Central Square stop on the Red Line. http://www.ploughandstars.com

Joyelle McSweeney is the author of The Red Bird and The Commandrine and Other Poems, both from Fence. She teaches at the University of Alabama and writes regular reviews for the Constant Critic. She recently co-founded Action Books (www.actionbooks.org), a new poetry and translation press.

Mark Lamoureux is a poet, critic and translator who lives in Astoria, NY. His work has appeared in numerous publications, both in print and online. He is an associate editor for Fulcrum Annual. He is the author of three chapbooks: City/Temple (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2003), 29 Cheeseburgers (Pressed Wafer, 2004) and Film Poems (Katalanche Press, 2005). His first full-length collection, Astrometry Organon is due out from Spuyten Duyvil/Meeting Eyes Bindery in the winter of 2006.

For more info contact:

John Mulrooney - jmulroon2002@yahoo.com

Michael Carr - cancelaspirin@gmail.com

Sincerely,

Yr Prodigal Son

May 11, 2006

The following is a piece I wrote for a class I had this semester on the memoir genre. I am thinking about expanding it into a full-on "ekphrastic memoir" at some later date, perhaps this summer, incorporating some of the stuff I've already written about video games, etc. The level of candor in this piece is a little beyond what I ordinarily exhibit on the blog, however, I am pretty happy with the piece so I will post it here.

Sometime around my father's 45th year, he began seeing his childhood sweetheart. The problem was that he also had a wife and a child at the time. But the strength of those old memories that were once so dear to him and had been forgotten for so long was so great that they split his life in two. I watched my father and my soon-to-be stepmother travel a gauntlet of embarrassing nostalgia: they listened constantly to Buddy Holly and Patsy Cline records, watched nothing but old films from the 50's or films which dealt with 50's culture like The Big Chill and Back to the Future. The anthem of their relationship became the film Somewhere in Time, in which the protagonist wills himself into the past to woo an actress from a photograph with whom he is obsessed. They frequented those restaurants and stores around Connecticut that had remained relatively unchanged since the 50's. To a 12-year-old whose family existed in the present and had been disrupted, this behavior was beyond disgusting.

In my 34th year (the age my father was when I was born), I realize that my father's vault into his job, his factory, and his marriage at a relatively young age, his drastic abandonment of childish things had estranged him so much from that childhood universe (however fraught with uncertainty and difficulty as it may have been) that his return to the same could only be drastic and violent. And this is what happened, upon reading that his childhood sweetheart was in town for the funeral of her father. These memories of the past had slept within him for so long, unacknowledged, that their return could only have life-rending consequences.

It is perhaps for this reason that over the years I have obsessively maintained a conduit to the mythology of my childhood, periodically revisiting childhood texts (both literary and popular) and have filled the sacred site of my creativity, my office, with objects from that time. This practice, while not, as I perceive it, especially uncommon among adults, can be viewed with some derision by those most enthusiastically preoccupied with "being an adult," and I might add, those who seem most prone to world-shattering midlife crises.

My home office is littered with boxes of un-built model-kits, some of which I possessed as a child, and some of which I merely wished to possess. Their built prototypes, which occupied those long, dull summer vacations spent alone in an isolated house in the suburbs while my single working mother was at work have long since vanished. I have been amassing the kits for years, alongside assorted literature concerning fine-scale modeling with the intent, apparently, of reconstructing the kits with an aplomb that I did not possess as a child. This task, however, is relegated to some indeterminate time-future when "I have some extra time." I cannot honestly speculate when this time may occur. At present they seem to offer some kind of reassurance that someday I will have that kind of leisure, as I did as a child. Perhaps they represent some kind of urge to rebuild, literally and figuratively, my childhood years as an adult.

In a similar fashion, I have, over the years, been amassing what amounts to a journal of my thoughts concerning comic-book characters who were important to me as a child, and who served as models for aspects of my own character and the character of others in my life. My intent in this piece is to give voice to some of these texts and to give form to the amorphous project begun long ago, as well as to offer some thoughts on its persistence.

Seven years ago I wrote:

It really comes as no surprise to me that this summer of 1999 finds me turning an eye to the trappings of my younger days. Recently, my roommate Aaron and I found ourselves driving to the exciting suburb of Somerville, barely able to find our way with the butterflies in our stomachs and the hairs on our necks standing at attention. We were going to see the new Star Wars movie. Fear not, dear reader, enough attention is being paid to the pantheon of Lucasfilm that I will not subject you to any more musings on Darth Vader and company. I mention this only insofar as on the drive home, Aaron and I began talking about the fact that for the first time in our lives an icon from our youth was being truly re-visited, with the requisite attention by the media to a long-ago "time past." Events of our childhood were being discussed as "history." People our own age were bringing their own small children to be initiated into the cult of their youth. Grown men (myself included) were buying toys and telling stories, digging up anecdotes from their past. I found myself actually saying to someone, "when I was your age..."

It is important for us to remember the things that shaped us. As a writer these things are important to me, and as an "ordinary human," too. It is important to realize that, however old we are, we're still just kids on many levels. Accepting this is part of "growing up," part of being "made whole."

Thus I began a meditation on the comic-book characters of my childhood. What strikes me now about these paragraphs is my dichotomization of "writer" and "ordinary human," and the relevance of that dichotomy in thinking about my analysis of my empathy toward those characters who were decidedly not "ordinary humans." Another obsessive part of me deems the present an appropriate time for the exhumation of this narrative given that this past summer George Lucas released the final act of his 20-year film cycle, bringing to a close the sweep of a narrative whose cultural force I do not need to explain here. Additionally, the third film about Marvel Comics' X-Men, who figure prominently in my meditation, is due out this summer. Perhaps 2006 is a logical interval to fix my own thoughts on the subject in time.

DAS UNHEIMLICHE: THE UNCANNY X-MEN

I was a sickly kid, or rather I was a nervous, excitable kid prone to fits of hypochondria and throwing up in the morning from the sheer anxiety of facing another day of frustration and torment at school. My hypochondria is an inherited trait, and consequently, I spent a lot of time being rushed to the pediatrician by my mother. The pediatrician did his best to prescribe doses of flat Coke and Jell-O water and general relaxation.

Down the street from Dr. Horton's office was a convenience store that sold comic books. Whenever I was in the midst of these episodes, my mother would buy me comic books to read as I "convalesced," as well as plenty of junk food, which I, miraculously, seemed to have no problem keeping down. I spent lots of time in the screened-in porch beside my house immersed in the fantastic stories of the X-Men and others as an alternative to school. At least I wasn't watching television.

I remember going to the dictionary one day during one of my sanctioned truancies to finally look up the word "uncanny." I remember skimming through the heavy, grown-up book and being filled with the same wonder as when I was following the lives of my favorite demi-humans. Stan Lee's sports-announcer alliteration and near-malapropisms continually sent me to the great tome to figure out what he was saying.

In my 1999 musings on the X-Men I focused primarily on their catalyzation of my interest in words and the oblique enhancement of my vocabulary comic books provided, and my knowledge of mythology, since mythological figures frequently appeared within their pages. While these are important facts, what interests me at present are the forces whereby I found myself in the screen-porch reading the X-Men, listening to the sound of the gypsy moths munching on the trees in the yard and eating peanut-butter filled Hostess cakes instead of being in school, and my particular interest in these particular characters, as opposed to the more popular (at the time, at least) ones like Spiderman and Superman.

Serendipitously, I need not go much further than my favorite super-team's appropriate epithet, "The Uncanny X-Men." The German word unheimlich, traditionally translated as "uncanny" in English has, as its root, the home. The uncanny pertains to the notion that there is something "not right" in "the home." It is the estranged familiar.

Indeed, at this time my familiar world was beginning to become strange. To this day, it is unclear to me during which year, specifically, my father began his affair with my stepmother, but reverse conjecture places it in the vicinity of 1984, when, in sixth grade, it was revealed to me that my father had a mistress and would be leaving the house. The affair had been going on for a number of years at that point, putting its genesis around the time (4th and 5th grade) that I began my screen porch sojourns with the Uncanny X-men.

I can recall an amorphous sense of anxiety pervading those years, inspired by numerous behind-closed-doors whispering sessions between my mother and father, the occasion for which was never revealed to me at the time. I began to dream that my mother was pregnant with a kind of demon-child who would usurp my place in the family structure (I was an only child). This anxiety inspired in me a predilection for nervous eating, and I began to put on weight, making me the brunt of cruel jokes and remarks in the classroom. Also, due to the conditions at home, I was no longer permitted to have classmates over to the house and I began to drift away from my peers. Years later, my mother would inform me that the community was well aware of my father's behavior well in advance of my own knowledge of it. Tolland, Connecticut was a small town and people were talking, but not to me. All of this perpetuated a general air of unease and secrecy--uncaniness, unease about the home.

The X-Men were a team of superheroes whose powers were derived genetically. They were "mutants" and suffered, continually, the scorn of those ordinary humans who their adventures and conflicts with all kinds of foes (some of them other "bad" mutants) were aimed at protecting. They were a team of "freaks," and consequently spoke to my own feelings of freakishness and isolation. Here was company where the brainy fat kid with a philandering father could feel at home. One was a Russian who could turn his body into living metal, whose girlfriend was a pretty Jewish girl who could turn her body intangible (her name was Ariel!). One was a Canadian with regenerative powers and claws that extended from his knuckles. One was an African woman with pupil-less eyes who could control the weather. One was a man whose eyes emitted destructive beans of energy unless shielded by special sunglasses. Their leader was a telepathic man in a wheelchair. And one was a feral German with blue fur and a tail who could teleport from one place to another. He was the most freakish of all, and my favorite.

THE DEMON-PRIEST: NIGHTCRAWLER

The X-Men were gods to me and Nightcrawler was the head of the pantheon. The few friends I had idolized Spiderman, the wiseguy, the Hulk, the brute-of-few words, and Iron Man, the playboy. My heart was with Nightcrawler, the freak. I took comfort in his sinister appearance that hid a kind heart and a quick wit. There are many people in the world with much more terrible things wrong with them than I perceived were wrong with me at the time, however, I can honestly say at that age I was not much to look at. I was a chubby kid with gangly arms and legs, an unseemly shock of bright red hair and sickly pale complexion. I also had fangs. Due to the fact that we had no money for an orthodontist, my canines were crowded out of the rest of my teeth, taking up residence about a half-an-inch higher than the others, in precisely the position where one found fangs on vampires, and Nightcrawler as well. The total package made me the brunt of countless childhood tortures. We've all been through them, but they hit me pretty hard because I had tangible evidence upon which to base my own feelings of being "deformed." Notably, I was "deformed" in a manner similar to my hero, who was also powerful, smart and moral, and his fellow X-Men loved him. He even had a girlfriend. I can remember fantasizing about Nightcrawler teleporting in to beat the snot out of the neighborhood bullies, my tormentors, placing a three-fingered hand on my shoulder and stating, "We sure showed them, mein freund. Come and live with us, we will teach you to defend yourself, we won't mock your hideous appearance, after all, we are so alike, you and I."

I had not thought of my snaggle-tooth for years until going through my files for pieces about Nightcrawler. It is relevant to note that my feelings of freakishness did not necessarily subside with the end of puberty and a growth-spurt that transformed my pudgy-gangliness to tall-and-awkwardness. Throughout my twenties, my dental woes caused me considerable consternation. My bad teeth required frequent and expensive intervention by the dentist in order to keep them from falling out of my mouth. At his time, such treatments were often beyond my modest means, and I endured any number of periods of pain, discomfort and frustration, which resulted in an obsession over the cosmetic peculiarities of my mouth. These were a source of constant anxiety during my dating years, an icon by which I dredged up deep-rooted feelings of Otherness and deformity. As friends were getting married and making money hand-over-fist during the Internet boom, my relative poverty and single-ness caused me no shortage of alarm. The Fat Kid had become the Starving Writer and the Depressive, which did not take me so far away from my archetypal hero, Nightcrawler.

These feelings of Otherness would manifest themselves severely during bouts of then-untreated depression. At these times, I would still find solace in the stories about my old friend. At the time, though, I had glossed over what, to my present mind, is one of the most compelling aspects of his character. Nightcrawler was deeply religious. In the context of the comic book, it was posited that the persecution he suffered at the hands of religious mobs in rural Germany caused him to seek refuge in a church, whereby he became acquainted with the Holy Spirit, which was capable of loving even him in his hideousness. If Lucifer was a fallen angel, Nightcrawler was his foil--the elevated demon. (In one story, it is Nightcrawler's faith in the cross that allows a particularly tenacious vampire to be defeated, the traditional cross-and-stake method of vampire removal being powerless in the hands of his teammates who did not believe in the power of the image.)

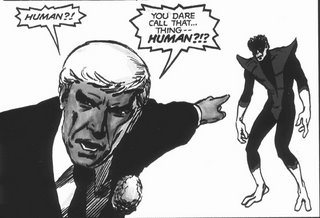

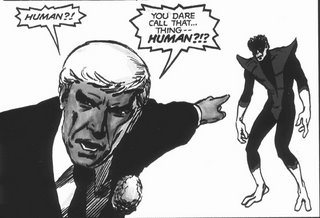

Being, at 34, an agnostic-bordering-on-belief, I begin to wonder why this particular aspect of the character escaped me for so many years. The simple message put forward by the comics was that religion was a balm to Nightcrawler's feelings of aloneness and Otherness. I am left to wonder why, in the deepest recesses of my depression, it never dawned upon me to seek transcendence by way of belief in something beyond myself and my pain--a compassion that touches every being no matter how abject and alone they are. Despite my leanings toward the spiritual, true belief is inhibited by my general cynicism and my materialism, and a disdain for the negative effects of religion upon our world. These negative effects are a phenomenon the comic book itself saw fit to address--in the image at the beginning of this section from the graphic novel God Loves, Man Kills, in which a fundamentalist preacher calls for the extinction of the mutants singles out the most faithful of the X-Men, Nightcrawler, to ridicule. Throughout the course of this adventure, Nightcrawler's goodwill and faith do not desert him. There may still be something to learn from my blue-furred friend.

It should come as no surprise that, given his numerous extraordinary qualities, Nightcrawler also found for himself a love interest during the course of the narrative. Nightcrawler's girlfriend, Amanda Sefton, was an airline stewardess who would later be given powers of her own and join him in his fantastic exploits. Being the paramour of my adolescent hero, one would might have expected me to have grown attached to the character's love interest as well, but I found myself with little to no interest in Nightcrawler's steady. She seemed far too ordinary and uninteresting. In fact, I found myself resenting the fact that the writers of the comic did not provide my favorite character with a more suitable companion. This was likely due to the fact that the recipient of my adolescent amorous fantasies was to be found elsewhere...

GOOD GIRLS GONE BAD: DARK PHOENIX

My mother never really recovered from her divorce. Withdrawn and passive to begin with, I watched her go from reticent, to sullen, to despairing. Being forced to join the workforce after 20 or so years, she had little in the way of marketable job skills, and still less in the way of self-esteem and confidence to talk her way through the situation. Beginning as a temporary, she began her professional career as an administrative assistant, routinely taken advantage of, abused and generally mistreated by a series of private-sector petty dictators. During this time she suffered from severe depression coupled with anxiety, culminating in anxiety attacks which she believed to be cardiac arrest. During these attacks she would implore her 12-year-old son to call 9-1-1. Which I invariably did following vain attempts to convince her that perhaps it was something else that was wrong. The ambulance would come, and I would spend a number of days at the neighbor's house. She would return from these hospital visits dazed and demoralized. To this day, I do not understand why her problems were not correctly diagnosed and treated. These experiences, which the doctors dismissed as "all in her head," eroded what little was left of her self-esteem. She was not only desperate, but she also believed herself to be crazy.

Just as her many years as a housewife did not prepare her for the workforce, they also did not prepare her for life as a single woman, or a single mother. Throughout her life, periods of partnerlessness longer than a month or two have left my mother paralyzed by fear. Her solution to this problem is to attach herself to whichever available male in her life is in a situation enabling him to attempt to be in a relationship with her. The net result of this has been a series of affairs with individuals about whom my grandfather would euphemistically state, "She could do better for herself."

Several months following the divorce, my mother began dating a man who worked in the electronics department of the garment-machinery firm for which she was working. This man referred to himself (and requested that others refer to him also) as Big Al. Said moniker was by no means ironic, as Big Al weighed in at around 300 pounds. He was about 10 years my mother's senior and possessed of a nebulous past filled with details which no-one, not even my mother was able to corroborate. Big Al was of American Indian descent, had at one time been a bodybuilder and professional wrestler, had been a ball-turret gunner in World War II, had borderline psychic abilities and had once fended off an entire mob of angry black men (Big Al used the term "Porch Monkeys" to refer to them) with a crowbar. (In regard to these facts my grandfather would state, somewhat less euphemistically, "That fat bastard is full of shit.") Whatever the real truths about his past were, the facts of his present were indisputable: he was racist, sexist, homophobic, jingoistic, ham-fisted and brutal. I've mentioned that he hated African Americans; he also hated cripples ("Useless People"), men with beards ("Fuzzy Faced Assholes"), people who had gone to college ("BS stands for 'bullshit' and PhD stands for 'piled high and deep'") and the French ("They fight with their feet and fuck with their mouths.") He also had not much use for my mother's strange and precocious son, the one person who stood between his sole ownership of his incredible good fortune, my mother.

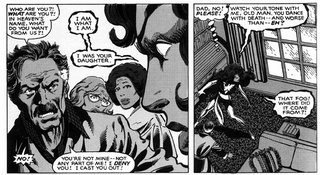

Big Al's antagonism of me stopped short of physical abuse, but during the years of their relationship I found myself wishing that my mother would realize take a good look Big Al and his ignorant hatred and look to find herself a more suitable companion, given that she is an open, accepting and intelligent person. However, the wound in her soul that was the cause of her psychological woes seemingly prevented her from realizing the absurdity in her choice of mates and incapable of standing up for me in the face of Big Al's wrath. A wrath which I increasingly found myself the brunt of as I began to get older and began to question my sexuality, became interested in Communism, the occult and punk rock. I was on my way to becoming a more or less garden-variety teenage intellectual and rebel, a character who had no place in Big Al's little world and elicited in him a particularly intense rage and scorn. It is also relevant to note that my burgeoning rebelliousness inspired a similar reaction in my own father, as well as my peers in school. I was alone. My mother's lack of participation in the increasingly unhealthy dynamic between Big Al and I, and her general predilection towards becoming a victim inspired in me a slight (although only slight) resentment, and, more intensely, an obsession with brazen, troubled and rebellious girls and women, women who were, sacredly, Nothing Whatsoever Like My Mother.

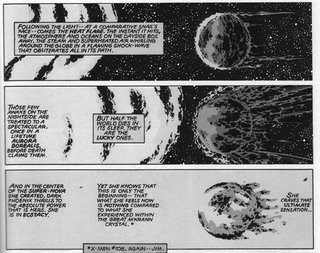

One can see the prototype of said inclination in my youthful fascination with another of the characters from the X-Men: Jean Grey, who would become the Dark Phoenix. Being at the time a medium concerned primarily with the whims and fantasies of adolescent and teenage boys, the comics industry of the 1980s can hardly be seen to have been a bastion of feminism. With its provision of ample bosoms, skin-tight costumes and its agonistic storylines it was not much of an antithesis to the worldview of Big Al, my father and others. However, perhaps as a symptom of the mainstream incorporation of 3rd wave feminism, women in comic books in the 1980s were beginning to experience a certain kind of transformation. While not emancipated from the ubiquitous skin-tight unitards and minidresses, the female characters in comics in the 1980s were beginning to emerge from their marginal roles as the girlfriends of the likes of Superman and Spiderman, and a little later the fey heroines of the 70's: "Invisible Girl," "The Wasp" and the earliest incarnation of Jean Grey, "Marvel Girl." The female comic book characters of the 80's were granted world-shattering superpowers and bellicose attitudes along with their idealized physical forms.

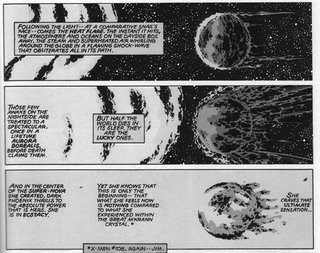

Marvel Girl was the love-interest of Cyclops, the hierarchical and pedantic leader of the X-Men. Her early abilities and appearance were the staples of silver-age comics heroines, mind-reading and telekinetic abilities paired with a yellow domino mask and a green minidress. The storyline that resulted her becoming the Dark Phoenix character involved the transformation of Marvel Girl into a sinister and omniscient being who tries to kill all of her friends (she reserved a particular rage for her former boyfriend) and eventually must be destroyed due to her threat to the entire fabric of the space-time continuum. Additionally, she was finally given a costume with pants.

Despite my love of the X-Men themselves, I could not help but to harbor a slight desire that Dark Phoenix would actually win their epic battle. Most likely because I subconsciously wished that my mother would undergo a similar transformation and do away with her own erstwhile companion. I was also fascinated with Dark Phoenix's stylized dialogue and the particular sympathy and interest that the writers showed for their villain. She was my first encounter with the literary anti-hero. As I wrote in 1998:

Around the same time as my musings on my disfiguredness I also found myself in the midst of a moral and spiritual crisis. Just as I could detect in myself the stirrings of self-worth and compassion, I also was beginning to realize my own potential for anger and bitterness. A constellation of lifelong morbid fascinations were in the pangs of birth.

And so Jean Grey aka Phoenix aka Dark Phoenix became the poster girl for my own moral dilemmas. What I was doing in the basement and the shower felt somehow wrong to me, but at the same time it felt quite good. Jean Grey was evidently turning into a villain, but at the same time she was becoming more and more attractive to my 12-year-old sensibilities. She was evil, but she was beautiful and powerful, seeming to remain the same person, but different somehow. My conundrum both intrigued and disgusted me. I was obviously a bad person if I still felt something in me stirring at the notion of Dark Phoenix when quite obviously she was going to eat the universe and her friends too. Yes, my first Bad Girl crush was on a comic book character. Laugh if you want, but I would later find myself drawn to the same archetype ad infinitum. Dark Phoenix was my introduction to sinister hedonism and to people with a chip on their shoulders, more often than not, a large one.

Luckily, as I grew older I would realize that intellectual and sexual liberation in a person could exist without a concurrent desire to destroy themselves and the universe, perhaps predicated by my own determination that the universe and I might be worthy of continued existence. My conception of an ideal partner mellowed from sociopathic to merely independent. Such early fetishizations are difficult to dispel, however and even in my adult life, in my mind's eye I still find myself in a planet-shattering embrace with Dark Phoenix and the similarly dark aspects of my own character.

MY ROBOT BODY: ROM THE SPACEKNIGHT

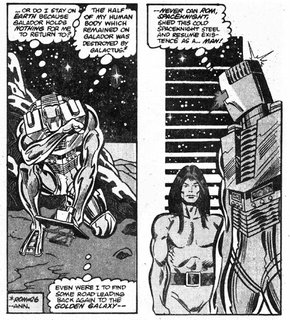

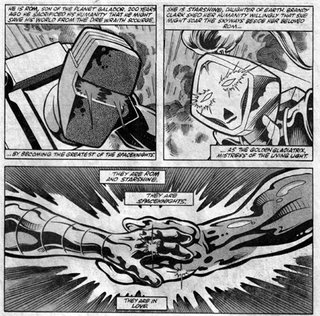

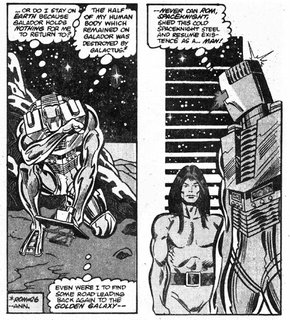

Another character to whom I attached particular importance as a child was ROM the Spaceknight. ROM began first as an electronic toy (one of the first of its kind) and shortly thereafter a comic book was written for the purpose of marketing the toy. As a very young child, I loved the toy and had in my possession issues of the comic book, which I did not completely follow or understand. Interest in the comic book far outstripped the toy--the comic series would continue for another 10 years or so, and I would revisit it later on, at the same time I was reading the X-Men in the screen porch.

The story of ROM concerned an alien prince who had given up his humanity to become a cybernetic hero in order to save his race from the clutches of shape-shifting monsters called the Dire Wraiths. These monsters found their way to Earth, where they were able to assume the countenance of ordinary humans. ROM made his way to earth in hot pursuit and there fell in love with a human woman named Brandy Clark, and subsequently began to wonder if giving up his human body to become a cyborg killing machine had really been such a great idea. The majority of the run of the comic presented ROM and Brandy's complex relationship amid the backdrop of ROM being periodically called upon the save the human race from the hidden menace of the Dire Wraiths.

The reasons for my interest in the book should be apparent. Here was another misunderstood hero fighting against covert and sinister forces who could assume the form of one's neighbors or, say, one's parents. As the sorrow that befell me due to the divorce and my subsequent home life began to take its toll, I became more sullen and withdrawn, and something in ROM's robotic character and his inability to rectify his rage and despair with his more tender feelings appealed to me. The character's missing mouth must have spoken to my own difficulties in expressing what was going on inside of me.

Following the initial news of my parents' imminent parting of ways, I stopped speaking for six months or so. Which isn't to say I entered into a monk-like vow of silence: I would converse enough to, say, ask for money to buy comic books, but I simply ceased to share my thoughts, emotions or anything else with my parents, friends or even pets. I entered into a silent psychic rapport with my toys, video games and comics. I felt my own armored shell begin to develop and I felt a sense of great frustration as my ability to communicate with others rapidly diminishing. Of course, there was no Brandy Clark involved, but my feeling of isolation from those I loved reached a similar desperate pitch.

I would later on find my own voice again through the process of writing poetry, but in my intimate and personal life, a certain lack of ability to communicate properly would continue to haunt me. As would the feeling of being armored, having steeled myself against a hurtful world and in doing so lost some capacity to experience love and joy. My ability to feel positive emotions had become somehow damaged. Also, the potential monster that lurked behind my friends, lovers and associates was, for many years, still quite palpably real.

I would eventually learn that this anhedonia was a symptom of severe depression, which I would treat on-and-off with various medications, either self-administered in the form of alcohol, or under the care of a psychiatrist. None of these ever really to dispelled my feelings of being trapped in a body that wasn't mine that had lost its ability to feel. Additionally, my vocation as a poet would put up a barrier between myself and "normal people" that I found hard to dispel, as well as alienating me from what was left of my family, my father in particular.

My detachment and lack of emotiveness continued to trouble me in my intimate relationships and my friendships, until, during my late 20's my depression landed me in the psychiatric ward of St. Elizabeth's hospital in Brookline, Massachusetts, following a particularly egregious period of despair, drinking and isolation following the dissolution of a relationship with yet another Dark Phoenix. My time in the hospital, with a roommate who had been so severely brain-damaged in a car accident that he could neither read nor write, and would begin each day by asking me what my name was as would have forgotten it since the day before, began to change my perception of myself as an irreparably damaged freak. Being amongst a population of more severely damaged individuals did not, however, diminish my empathization with or compassion for those who find themselves on the periphery of what our society deems "normal." Likewise, these icons of Otherness I describe here are never far from my thoughts, neither are the denizens of the ward at St. Elizabeth's.

Even with my depression at last successfully treated with the right mix of pyschopharmaceuticals, I still find myself contending with the ghost of ROM's robot armor, given that my emotional and erotic responses remain somewhat truncated, as side effects of my medication. Thus I am released from my universe-consuming despair, but still do not find myself in complete possession of my body. (One might see me as a kind of chemical cyborg, the functions of my brain augmented by technology, albeit microscopic compounds as opposed to a robotic suit of armor.) However, at present I find these to be merely hindrances and not outright obstacles to having the kind of life that my childhood heroes coveted.

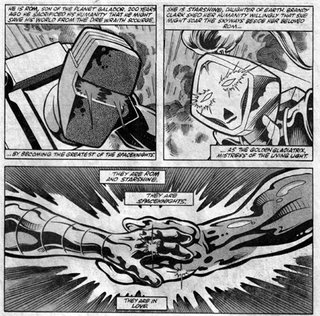

Likewise, I find there is no shortage of people who have had similar experiences with depression and medication who can relate to the events of my life. In the comic, ROM finally finds a kind of happiness when his human girlfriend is given a similar robot body. Despite the obvious limitations of such a relationship, perhaps he finally felt, to some degree, less alone--as I do, both in the presence of my real-life (and non-robotic) girlfriend and peers, as well as when I return to the pages of those texts that were such a comfort to me in my youth.

ON BECOMING HUMAN

Sometime around my father's 45th year, he began seeing his childhood sweetheart. The problem was that he also had a wife and a child at the time. But the strength of those old memories that were once so dear to him and had been forgotten for so long was so great that they split his life in two. I watched my father and my soon-to-be stepmother travel a gauntlet of embarrassing nostalgia: they listened constantly to Buddy Holly and Patsy Cline records, watched nothing but old films from the 50's or films which dealt with 50's culture like The Big Chill and Back to the Future. The anthem of their relationship became the film Somewhere in Time, in which the protagonist wills himself into the past to woo an actress from a photograph with whom he is obsessed. They frequented those restaurants and stores around Connecticut that had remained relatively unchanged since the 50's. To a 12-year-old whose family existed in the present and had been disrupted, this behavior was beyond disgusting.

In my 34th year (the age my father was when I was born), I realize that my father's vault into his job, his factory, and his marriage at a relatively young age, his drastic abandonment of childish things had estranged him so much from that childhood universe (however fraught with uncertainty and difficulty as it may have been) that his return to the same could only be drastic and violent. And this is what happened, upon reading that his childhood sweetheart was in town for the funeral of her father. These memories of the past had slept within him for so long, unacknowledged, that their return could only have life-rending consequences.

It is perhaps for this reason that over the years I have obsessively maintained a conduit to the mythology of my childhood, periodically revisiting childhood texts (both literary and popular) and have filled the sacred site of my creativity, my office, with objects from that time. This practice, while not, as I perceive it, especially uncommon among adults, can be viewed with some derision by those most enthusiastically preoccupied with "being an adult," and I might add, those who seem most prone to world-shattering midlife crises.

My home office is littered with boxes of un-built model-kits, some of which I possessed as a child, and some of which I merely wished to possess. Their built prototypes, which occupied those long, dull summer vacations spent alone in an isolated house in the suburbs while my single working mother was at work have long since vanished. I have been amassing the kits for years, alongside assorted literature concerning fine-scale modeling with the intent, apparently, of reconstructing the kits with an aplomb that I did not possess as a child. This task, however, is relegated to some indeterminate time-future when "I have some extra time." I cannot honestly speculate when this time may occur. At present they seem to offer some kind of reassurance that someday I will have that kind of leisure, as I did as a child. Perhaps they represent some kind of urge to rebuild, literally and figuratively, my childhood years as an adult.

In a similar fashion, I have, over the years, been amassing what amounts to a journal of my thoughts concerning comic-book characters who were important to me as a child, and who served as models for aspects of my own character and the character of others in my life. My intent in this piece is to give voice to some of these texts and to give form to the amorphous project begun long ago, as well as to offer some thoughts on its persistence.

Seven years ago I wrote:

It really comes as no surprise to me that this summer of 1999 finds me turning an eye to the trappings of my younger days. Recently, my roommate Aaron and I found ourselves driving to the exciting suburb of Somerville, barely able to find our way with the butterflies in our stomachs and the hairs on our necks standing at attention. We were going to see the new Star Wars movie. Fear not, dear reader, enough attention is being paid to the pantheon of Lucasfilm that I will not subject you to any more musings on Darth Vader and company. I mention this only insofar as on the drive home, Aaron and I began talking about the fact that for the first time in our lives an icon from our youth was being truly re-visited, with the requisite attention by the media to a long-ago "time past." Events of our childhood were being discussed as "history." People our own age were bringing their own small children to be initiated into the cult of their youth. Grown men (myself included) were buying toys and telling stories, digging up anecdotes from their past. I found myself actually saying to someone, "when I was your age..."

It is important for us to remember the things that shaped us. As a writer these things are important to me, and as an "ordinary human," too. It is important to realize that, however old we are, we're still just kids on many levels. Accepting this is part of "growing up," part of being "made whole."

Thus I began a meditation on the comic-book characters of my childhood. What strikes me now about these paragraphs is my dichotomization of "writer" and "ordinary human," and the relevance of that dichotomy in thinking about my analysis of my empathy toward those characters who were decidedly not "ordinary humans." Another obsessive part of me deems the present an appropriate time for the exhumation of this narrative given that this past summer George Lucas released the final act of his 20-year film cycle, bringing to a close the sweep of a narrative whose cultural force I do not need to explain here. Additionally, the third film about Marvel Comics' X-Men, who figure prominently in my meditation, is due out this summer. Perhaps 2006 is a logical interval to fix my own thoughts on the subject in time.

DAS UNHEIMLICHE: THE UNCANNY X-MEN

I was a sickly kid, or rather I was a nervous, excitable kid prone to fits of hypochondria and throwing up in the morning from the sheer anxiety of facing another day of frustration and torment at school. My hypochondria is an inherited trait, and consequently, I spent a lot of time being rushed to the pediatrician by my mother. The pediatrician did his best to prescribe doses of flat Coke and Jell-O water and general relaxation.

Down the street from Dr. Horton's office was a convenience store that sold comic books. Whenever I was in the midst of these episodes, my mother would buy me comic books to read as I "convalesced," as well as plenty of junk food, which I, miraculously, seemed to have no problem keeping down. I spent lots of time in the screened-in porch beside my house immersed in the fantastic stories of the X-Men and others as an alternative to school. At least I wasn't watching television.

I remember going to the dictionary one day during one of my sanctioned truancies to finally look up the word "uncanny." I remember skimming through the heavy, grown-up book and being filled with the same wonder as when I was following the lives of my favorite demi-humans. Stan Lee's sports-announcer alliteration and near-malapropisms continually sent me to the great tome to figure out what he was saying.

In my 1999 musings on the X-Men I focused primarily on their catalyzation of my interest in words and the oblique enhancement of my vocabulary comic books provided, and my knowledge of mythology, since mythological figures frequently appeared within their pages. While these are important facts, what interests me at present are the forces whereby I found myself in the screen-porch reading the X-Men, listening to the sound of the gypsy moths munching on the trees in the yard and eating peanut-butter filled Hostess cakes instead of being in school, and my particular interest in these particular characters, as opposed to the more popular (at the time, at least) ones like Spiderman and Superman.

Serendipitously, I need not go much further than my favorite super-team's appropriate epithet, "The Uncanny X-Men." The German word unheimlich, traditionally translated as "uncanny" in English has, as its root, the home. The uncanny pertains to the notion that there is something "not right" in "the home." It is the estranged familiar.

Indeed, at this time my familiar world was beginning to become strange. To this day, it is unclear to me during which year, specifically, my father began his affair with my stepmother, but reverse conjecture places it in the vicinity of 1984, when, in sixth grade, it was revealed to me that my father had a mistress and would be leaving the house. The affair had been going on for a number of years at that point, putting its genesis around the time (4th and 5th grade) that I began my screen porch sojourns with the Uncanny X-men.

I can recall an amorphous sense of anxiety pervading those years, inspired by numerous behind-closed-doors whispering sessions between my mother and father, the occasion for which was never revealed to me at the time. I began to dream that my mother was pregnant with a kind of demon-child who would usurp my place in the family structure (I was an only child). This anxiety inspired in me a predilection for nervous eating, and I began to put on weight, making me the brunt of cruel jokes and remarks in the classroom. Also, due to the conditions at home, I was no longer permitted to have classmates over to the house and I began to drift away from my peers. Years later, my mother would inform me that the community was well aware of my father's behavior well in advance of my own knowledge of it. Tolland, Connecticut was a small town and people were talking, but not to me. All of this perpetuated a general air of unease and secrecy--uncaniness, unease about the home.

The X-Men were a team of superheroes whose powers were derived genetically. They were "mutants" and suffered, continually, the scorn of those ordinary humans who their adventures and conflicts with all kinds of foes (some of them other "bad" mutants) were aimed at protecting. They were a team of "freaks," and consequently spoke to my own feelings of freakishness and isolation. Here was company where the brainy fat kid with a philandering father could feel at home. One was a Russian who could turn his body into living metal, whose girlfriend was a pretty Jewish girl who could turn her body intangible (her name was Ariel!). One was a Canadian with regenerative powers and claws that extended from his knuckles. One was an African woman with pupil-less eyes who could control the weather. One was a man whose eyes emitted destructive beans of energy unless shielded by special sunglasses. Their leader was a telepathic man in a wheelchair. And one was a feral German with blue fur and a tail who could teleport from one place to another. He was the most freakish of all, and my favorite.

THE DEMON-PRIEST: NIGHTCRAWLER

The X-Men were gods to me and Nightcrawler was the head of the pantheon. The few friends I had idolized Spiderman, the wiseguy, the Hulk, the brute-of-few words, and Iron Man, the playboy. My heart was with Nightcrawler, the freak. I took comfort in his sinister appearance that hid a kind heart and a quick wit. There are many people in the world with much more terrible things wrong with them than I perceived were wrong with me at the time, however, I can honestly say at that age I was not much to look at. I was a chubby kid with gangly arms and legs, an unseemly shock of bright red hair and sickly pale complexion. I also had fangs. Due to the fact that we had no money for an orthodontist, my canines were crowded out of the rest of my teeth, taking up residence about a half-an-inch higher than the others, in precisely the position where one found fangs on vampires, and Nightcrawler as well. The total package made me the brunt of countless childhood tortures. We've all been through them, but they hit me pretty hard because I had tangible evidence upon which to base my own feelings of being "deformed." Notably, I was "deformed" in a manner similar to my hero, who was also powerful, smart and moral, and his fellow X-Men loved him. He even had a girlfriend. I can remember fantasizing about Nightcrawler teleporting in to beat the snot out of the neighborhood bullies, my tormentors, placing a three-fingered hand on my shoulder and stating, "We sure showed them, mein freund. Come and live with us, we will teach you to defend yourself, we won't mock your hideous appearance, after all, we are so alike, you and I."

I had not thought of my snaggle-tooth for years until going through my files for pieces about Nightcrawler. It is relevant to note that my feelings of freakishness did not necessarily subside with the end of puberty and a growth-spurt that transformed my pudgy-gangliness to tall-and-awkwardness. Throughout my twenties, my dental woes caused me considerable consternation. My bad teeth required frequent and expensive intervention by the dentist in order to keep them from falling out of my mouth. At his time, such treatments were often beyond my modest means, and I endured any number of periods of pain, discomfort and frustration, which resulted in an obsession over the cosmetic peculiarities of my mouth. These were a source of constant anxiety during my dating years, an icon by which I dredged up deep-rooted feelings of Otherness and deformity. As friends were getting married and making money hand-over-fist during the Internet boom, my relative poverty and single-ness caused me no shortage of alarm. The Fat Kid had become the Starving Writer and the Depressive, which did not take me so far away from my archetypal hero, Nightcrawler.

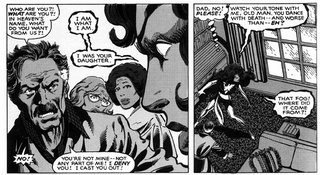

These feelings of Otherness would manifest themselves severely during bouts of then-untreated depression. At these times, I would still find solace in the stories about my old friend. At the time, though, I had glossed over what, to my present mind, is one of the most compelling aspects of his character. Nightcrawler was deeply religious. In the context of the comic book, it was posited that the persecution he suffered at the hands of religious mobs in rural Germany caused him to seek refuge in a church, whereby he became acquainted with the Holy Spirit, which was capable of loving even him in his hideousness. If Lucifer was a fallen angel, Nightcrawler was his foil--the elevated demon. (In one story, it is Nightcrawler's faith in the cross that allows a particularly tenacious vampire to be defeated, the traditional cross-and-stake method of vampire removal being powerless in the hands of his teammates who did not believe in the power of the image.)

Being, at 34, an agnostic-bordering-on-belief, I begin to wonder why this particular aspect of the character escaped me for so many years. The simple message put forward by the comics was that religion was a balm to Nightcrawler's feelings of aloneness and Otherness. I am left to wonder why, in the deepest recesses of my depression, it never dawned upon me to seek transcendence by way of belief in something beyond myself and my pain--a compassion that touches every being no matter how abject and alone they are. Despite my leanings toward the spiritual, true belief is inhibited by my general cynicism and my materialism, and a disdain for the negative effects of religion upon our world. These negative effects are a phenomenon the comic book itself saw fit to address--in the image at the beginning of this section from the graphic novel God Loves, Man Kills, in which a fundamentalist preacher calls for the extinction of the mutants singles out the most faithful of the X-Men, Nightcrawler, to ridicule. Throughout the course of this adventure, Nightcrawler's goodwill and faith do not desert him. There may still be something to learn from my blue-furred friend.

It should come as no surprise that, given his numerous extraordinary qualities, Nightcrawler also found for himself a love interest during the course of the narrative. Nightcrawler's girlfriend, Amanda Sefton, was an airline stewardess who would later be given powers of her own and join him in his fantastic exploits. Being the paramour of my adolescent hero, one would might have expected me to have grown attached to the character's love interest as well, but I found myself with little to no interest in Nightcrawler's steady. She seemed far too ordinary and uninteresting. In fact, I found myself resenting the fact that the writers of the comic did not provide my favorite character with a more suitable companion. This was likely due to the fact that the recipient of my adolescent amorous fantasies was to be found elsewhere...

GOOD GIRLS GONE BAD: DARK PHOENIX

My mother never really recovered from her divorce. Withdrawn and passive to begin with, I watched her go from reticent, to sullen, to despairing. Being forced to join the workforce after 20 or so years, she had little in the way of marketable job skills, and still less in the way of self-esteem and confidence to talk her way through the situation. Beginning as a temporary, she began her professional career as an administrative assistant, routinely taken advantage of, abused and generally mistreated by a series of private-sector petty dictators. During this time she suffered from severe depression coupled with anxiety, culminating in anxiety attacks which she believed to be cardiac arrest. During these attacks she would implore her 12-year-old son to call 9-1-1. Which I invariably did following vain attempts to convince her that perhaps it was something else that was wrong. The ambulance would come, and I would spend a number of days at the neighbor's house. She would return from these hospital visits dazed and demoralized. To this day, I do not understand why her problems were not correctly diagnosed and treated. These experiences, which the doctors dismissed as "all in her head," eroded what little was left of her self-esteem. She was not only desperate, but she also believed herself to be crazy.

Just as her many years as a housewife did not prepare her for the workforce, they also did not prepare her for life as a single woman, or a single mother. Throughout her life, periods of partnerlessness longer than a month or two have left my mother paralyzed by fear. Her solution to this problem is to attach herself to whichever available male in her life is in a situation enabling him to attempt to be in a relationship with her. The net result of this has been a series of affairs with individuals about whom my grandfather would euphemistically state, "She could do better for herself."

Several months following the divorce, my mother began dating a man who worked in the electronics department of the garment-machinery firm for which she was working. This man referred to himself (and requested that others refer to him also) as Big Al. Said moniker was by no means ironic, as Big Al weighed in at around 300 pounds. He was about 10 years my mother's senior and possessed of a nebulous past filled with details which no-one, not even my mother was able to corroborate. Big Al was of American Indian descent, had at one time been a bodybuilder and professional wrestler, had been a ball-turret gunner in World War II, had borderline psychic abilities and had once fended off an entire mob of angry black men (Big Al used the term "Porch Monkeys" to refer to them) with a crowbar. (In regard to these facts my grandfather would state, somewhat less euphemistically, "That fat bastard is full of shit.") Whatever the real truths about his past were, the facts of his present were indisputable: he was racist, sexist, homophobic, jingoistic, ham-fisted and brutal. I've mentioned that he hated African Americans; he also hated cripples ("Useless People"), men with beards ("Fuzzy Faced Assholes"), people who had gone to college ("BS stands for 'bullshit' and PhD stands for 'piled high and deep'") and the French ("They fight with their feet and fuck with their mouths.") He also had not much use for my mother's strange and precocious son, the one person who stood between his sole ownership of his incredible good fortune, my mother.

Big Al's antagonism of me stopped short of physical abuse, but during the years of their relationship I found myself wishing that my mother would realize take a good look Big Al and his ignorant hatred and look to find herself a more suitable companion, given that she is an open, accepting and intelligent person. However, the wound in her soul that was the cause of her psychological woes seemingly prevented her from realizing the absurdity in her choice of mates and incapable of standing up for me in the face of Big Al's wrath. A wrath which I increasingly found myself the brunt of as I began to get older and began to question my sexuality, became interested in Communism, the occult and punk rock. I was on my way to becoming a more or less garden-variety teenage intellectual and rebel, a character who had no place in Big Al's little world and elicited in him a particularly intense rage and scorn. It is also relevant to note that my burgeoning rebelliousness inspired a similar reaction in my own father, as well as my peers in school. I was alone. My mother's lack of participation in the increasingly unhealthy dynamic between Big Al and I, and her general predilection towards becoming a victim inspired in me a slight (although only slight) resentment, and, more intensely, an obsession with brazen, troubled and rebellious girls and women, women who were, sacredly, Nothing Whatsoever Like My Mother.

One can see the prototype of said inclination in my youthful fascination with another of the characters from the X-Men: Jean Grey, who would become the Dark Phoenix. Being at the time a medium concerned primarily with the whims and fantasies of adolescent and teenage boys, the comics industry of the 1980s can hardly be seen to have been a bastion of feminism. With its provision of ample bosoms, skin-tight costumes and its agonistic storylines it was not much of an antithesis to the worldview of Big Al, my father and others. However, perhaps as a symptom of the mainstream incorporation of 3rd wave feminism, women in comic books in the 1980s were beginning to experience a certain kind of transformation. While not emancipated from the ubiquitous skin-tight unitards and minidresses, the female characters in comics in the 1980s were beginning to emerge from their marginal roles as the girlfriends of the likes of Superman and Spiderman, and a little later the fey heroines of the 70's: "Invisible Girl," "The Wasp" and the earliest incarnation of Jean Grey, "Marvel Girl." The female comic book characters of the 80's were granted world-shattering superpowers and bellicose attitudes along with their idealized physical forms.

Marvel Girl was the love-interest of Cyclops, the hierarchical and pedantic leader of the X-Men. Her early abilities and appearance were the staples of silver-age comics heroines, mind-reading and telekinetic abilities paired with a yellow domino mask and a green minidress. The storyline that resulted her becoming the Dark Phoenix character involved the transformation of Marvel Girl into a sinister and omniscient being who tries to kill all of her friends (she reserved a particular rage for her former boyfriend) and eventually must be destroyed due to her threat to the entire fabric of the space-time continuum. Additionally, she was finally given a costume with pants.

Despite my love of the X-Men themselves, I could not help but to harbor a slight desire that Dark Phoenix would actually win their epic battle. Most likely because I subconsciously wished that my mother would undergo a similar transformation and do away with her own erstwhile companion. I was also fascinated with Dark Phoenix's stylized dialogue and the particular sympathy and interest that the writers showed for their villain. She was my first encounter with the literary anti-hero. As I wrote in 1998:

Around the same time as my musings on my disfiguredness I also found myself in the midst of a moral and spiritual crisis. Just as I could detect in myself the stirrings of self-worth and compassion, I also was beginning to realize my own potential for anger and bitterness. A constellation of lifelong morbid fascinations were in the pangs of birth.

And so Jean Grey aka Phoenix aka Dark Phoenix became the poster girl for my own moral dilemmas. What I was doing in the basement and the shower felt somehow wrong to me, but at the same time it felt quite good. Jean Grey was evidently turning into a villain, but at the same time she was becoming more and more attractive to my 12-year-old sensibilities. She was evil, but she was beautiful and powerful, seeming to remain the same person, but different somehow. My conundrum both intrigued and disgusted me. I was obviously a bad person if I still felt something in me stirring at the notion of Dark Phoenix when quite obviously she was going to eat the universe and her friends too. Yes, my first Bad Girl crush was on a comic book character. Laugh if you want, but I would later find myself drawn to the same archetype ad infinitum. Dark Phoenix was my introduction to sinister hedonism and to people with a chip on their shoulders, more often than not, a large one.

Luckily, as I grew older I would realize that intellectual and sexual liberation in a person could exist without a concurrent desire to destroy themselves and the universe, perhaps predicated by my own determination that the universe and I might be worthy of continued existence. My conception of an ideal partner mellowed from sociopathic to merely independent. Such early fetishizations are difficult to dispel, however and even in my adult life, in my mind's eye I still find myself in a planet-shattering embrace with Dark Phoenix and the similarly dark aspects of my own character.

MY ROBOT BODY: ROM THE SPACEKNIGHT

Another character to whom I attached particular importance as a child was ROM the Spaceknight. ROM began first as an electronic toy (one of the first of its kind) and shortly thereafter a comic book was written for the purpose of marketing the toy. As a very young child, I loved the toy and had in my possession issues of the comic book, which I did not completely follow or understand. Interest in the comic book far outstripped the toy--the comic series would continue for another 10 years or so, and I would revisit it later on, at the same time I was reading the X-Men in the screen porch.

The story of ROM concerned an alien prince who had given up his humanity to become a cybernetic hero in order to save his race from the clutches of shape-shifting monsters called the Dire Wraiths. These monsters found their way to Earth, where they were able to assume the countenance of ordinary humans. ROM made his way to earth in hot pursuit and there fell in love with a human woman named Brandy Clark, and subsequently began to wonder if giving up his human body to become a cyborg killing machine had really been such a great idea. The majority of the run of the comic presented ROM and Brandy's complex relationship amid the backdrop of ROM being periodically called upon the save the human race from the hidden menace of the Dire Wraiths.

The reasons for my interest in the book should be apparent. Here was another misunderstood hero fighting against covert and sinister forces who could assume the form of one's neighbors or, say, one's parents. As the sorrow that befell me due to the divorce and my subsequent home life began to take its toll, I became more sullen and withdrawn, and something in ROM's robotic character and his inability to rectify his rage and despair with his more tender feelings appealed to me. The character's missing mouth must have spoken to my own difficulties in expressing what was going on inside of me.

Following the initial news of my parents' imminent parting of ways, I stopped speaking for six months or so. Which isn't to say I entered into a monk-like vow of silence: I would converse enough to, say, ask for money to buy comic books, but I simply ceased to share my thoughts, emotions or anything else with my parents, friends or even pets. I entered into a silent psychic rapport with my toys, video games and comics. I felt my own armored shell begin to develop and I felt a sense of great frustration as my ability to communicate with others rapidly diminishing. Of course, there was no Brandy Clark involved, but my feeling of isolation from those I loved reached a similar desperate pitch.

I would later on find my own voice again through the process of writing poetry, but in my intimate and personal life, a certain lack of ability to communicate properly would continue to haunt me. As would the feeling of being armored, having steeled myself against a hurtful world and in doing so lost some capacity to experience love and joy. My ability to feel positive emotions had become somehow damaged. Also, the potential monster that lurked behind my friends, lovers and associates was, for many years, still quite palpably real.

I would eventually learn that this anhedonia was a symptom of severe depression, which I would treat on-and-off with various medications, either self-administered in the form of alcohol, or under the care of a psychiatrist. None of these ever really to dispelled my feelings of being trapped in a body that wasn't mine that had lost its ability to feel. Additionally, my vocation as a poet would put up a barrier between myself and "normal people" that I found hard to dispel, as well as alienating me from what was left of my family, my father in particular.

My detachment and lack of emotiveness continued to trouble me in my intimate relationships and my friendships, until, during my late 20's my depression landed me in the psychiatric ward of St. Elizabeth's hospital in Brookline, Massachusetts, following a particularly egregious period of despair, drinking and isolation following the dissolution of a relationship with yet another Dark Phoenix. My time in the hospital, with a roommate who had been so severely brain-damaged in a car accident that he could neither read nor write, and would begin each day by asking me what my name was as would have forgotten it since the day before, began to change my perception of myself as an irreparably damaged freak. Being amongst a population of more severely damaged individuals did not, however, diminish my empathization with or compassion for those who find themselves on the periphery of what our society deems "normal." Likewise, these icons of Otherness I describe here are never far from my thoughts, neither are the denizens of the ward at St. Elizabeth's.

Even with my depression at last successfully treated with the right mix of pyschopharmaceuticals, I still find myself contending with the ghost of ROM's robot armor, given that my emotional and erotic responses remain somewhat truncated, as side effects of my medication. Thus I am released from my universe-consuming despair, but still do not find myself in complete possession of my body. (One might see me as a kind of chemical cyborg, the functions of my brain augmented by technology, albeit microscopic compounds as opposed to a robotic suit of armor.) However, at present I find these to be merely hindrances and not outright obstacles to having the kind of life that my childhood heroes coveted.

Likewise, I find there is no shortage of people who have had similar experiences with depression and medication who can relate to the events of my life. In the comic, ROM finally finds a kind of happiness when his human girlfriend is given a similar robot body. Despite the obvious limitations of such a relationship, perhaps he finally felt, to some degree, less alone--as I do, both in the presence of my real-life (and non-robotic) girlfriend and peers, as well as when I return to the pages of those texts that were such a comfort to me in my youth.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)